CALGARY — The death of Hanne Schafer was by any definition a nightmare.

Suffering from the painful, degenerative neurological disease ALS, the 66-year-old could communicate only by typing with some of the fingers on her left hand. Her husband had to regularly suction the saliva out of her throat so she wouldn't choke. He had to lift her onto the toilet so she could go to the bathroom.

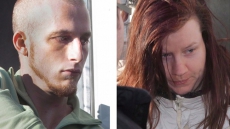

"She was like a butterfly trapped in a cocoon," recalled Daniel Laurin, who on Wednesday won in court the right to make his wife's name public so he could tell her story. "That's the way that she explained she felt."

As horribly difficult as international travel would have been, the Calgary psychologist had been planning to travel to Switzerland to have a physician-assisted death when she learned Canada's Supreme Court had ordered the federal government to come up with assisted-dying legislation.

Patients were told they could get permission from a judge while that was in the works, so Schafer, her husband, and their friend Mary Valentich, a social worker, started making calls.

"She decided to go to court instead of Switzerland," said Laurin. "It wasn't an easy thing to do. It was a very difficult and emotional thing for everybody."

Valentich said despite the efforts of a large group of friends, they were unable to find a Calgary doctor willing to help Shafer die. A doctor in Holland finally put them in touch with Dr. Ellen Wiebe, a Vancouver activist who believes strongly in the right to die and who, on Feb. 29, was at Shafer's side in the B.C. city when her life came to an end.

Valentich said the hurdles were constant. Getting a pharmacist to fill the prescription for her life-ending drugs was difficult and "even finding a lawyer to take on the case was not that straightforward."

When they went to court for permission to have a doctor help end Shafer's life, they ran into another snag. She asked for a publication ban on her name, with the intent it would expire at her death.

But Laurin said there was a misunderstanding, and he discovered that after her death the publication ban remained in force. That meant he couldn't even publish her obituary.

"Hanne was very well known here," he said. "She did a lot of good work, helped a lot of people. She wanted her story told."

On Wednesday, a judge agreed to lift the ban, though the court and medical documents in the case will remain sealed.

Laurin said he was glad to be able to finally talk about his wife, though he said Wednesday's victory does nothing to erase her loss and the terrible months leading up to her death.

"It should have been easier," he said. "Why does a person have to go through that?"

Valentich described her friend as a trailblazer who knew very well that her fight might stand to benefit others after she was gone.

"The way in which she was an agent of her own death was really very moving. It was a peaceful death, unlike some of the other deaths I've witnessed."

Shafer's husband agreed.

"Hanne was a very bright and very quick lady," he said. "Hanne, to me, was a genius. Very, very smart. She knew what she was doing. There was nothing wrong with her brain. She knew how she wanted it done, and when she decided to have it done, she wanted it done as quickly as possible."

He described with unabashed admiration the long hours of work she put into arranging her death, sitting on the computer for hours tapping out emails and searching for information with the few fingers she had that worked.

She should, he said, have been able to die in her own bed.

Now, he looks forward to continuing his wife's fight.

"I want to be an activist for people who are sick and who are suffering," he said adamantly. "It's not right, the way the government is handling this. Nobody wants to get their hands dirty at all. They all want to give it to a committee, and then the committee's going to give it to somebody else."

It was only at the suggestion that she was lucky to have such a loving and supportive husband that Laurin broke down in tears.

"Well," he said between sobs, "I was lucky I had her."