OTTAWA - Canada is all but certain to miss its Copenhagen Accord target to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 2020, the country's environmental watchdog warned Tuesday.

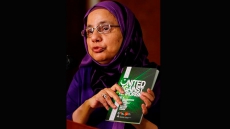

And not only has the Harper government failed to introduce regulations to limit the amount carbon dioxide produced by the oil and gas sector, the fastest growing emitter, it "does not have an overall plan that maps out how Canada will achieve this target," Julie Gelfand said in her first report as commissioner of the environment and sustainable development.

Under the accord, which the government signed in lieu of participating in the Kyoto Protocol, greenhouse gas production was to be cut to 17 per cent below 2005 levels by 2020.

Gelfand's predecessor warned in 2012 that the government was off course and "two years later, the evidence is stronger that growth in emissions will not be reversed in time and that the target will be missed," said the report.

The government has introduced regulations to govern the automotive and transportation sector, the biggest source of emissions, as well as the area of electricity production.

But Gelfand's report says that while regulations for coal-fired plants are in place, emissions have yet to be reduced because "performance standards take effect only in July 2015, and only apply to new plants or to existing plants when they reach the end of their useful life."

Using Environment Canada data, the commissioner estimated that by 2020, greenhouse gas production in the oil and gas sector will be 27 megatonnes higher than it was in 2012. That's the biggest increase of any sector.

Gelfand also found that detailed, proposed regulations are sitting on the environment minister's desk, but the "federal government has consulted on them only privately, mainly using a small working group of one province and selected industry representatives."

Federal officials told the commissioner implementation has been delayed over "concern about whether regulations would make Canadian companies in the sector less able to compete with their U.S. counterparts," the report said.

Timelines to put reduction measures in place have not been met and there has been little in the way of consultation with the provinces on how to achieve the national emissions target, Gelfand said.

The commissioner's report also tore a strip off Environment Canada, Transport Canada and Fisheries and Oceans, saying mapping and icebreaking services in the Arctic are not what they should be at a time of growing marine traffic in the Far North.

For almost a decade, the government has been talking up issues of sovereignty and resource development in the Arctic, but many high-traffic, high-risk areas remain inadequately surveyed and most of the available charts may not be current or reliable, the report found.

"The Canadian Coast Guard cannot provide assurance to mariners that aids to navigation meet their needs for safe and efficient navigation in high-risk areas of the Arctic," Gelfand concluded.

The government did receive good marks for how it is monitoring development of Alberta's oilsands, but Gelfand said more effort needs to be made to consult First Nations and to incorporate traditional ecological monitoring knowledge into Environment Canada's monitoring activities.

But she warned that plans to continue monitoring the project are unclear after March 2015.

When it comes to deciding which projects are designated for environmental assessment, the rationale is unclear, the commissioner also noted.

In addition, federal departments need to do a better job of flagging individual ministers about the environmental impact of their decisions and strategic environmental assessments are often not stapled to projects put before cabinet.