OTTAWA — Not only were Canadian officials scrambling to limit problems for travellers, they were simply trying to grasp what was going on when the Trump administration issued an executive order last year banning people from seven predominantly Muslim countries from entering the United States.

Newly released internal notes from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security reveal Canadian government officials fired off a list of 16 detailed questions with the aim of figuring out the order's impact on everything from refugee claims to biometric tracking.

The records were recently released to The Canadian Press in response to a February 2017 request under the U.S. Freedom of Information Act, asking for materials used to brief then-homeland secretary John Kelly in advance of phone calls with Canadian Public Safety Minister Ralph Goodale.

Some 400,000 people and more than $2 billion worth of goods and services cross the Canada-U.S. border every day.

The order — officially the Executive Order on Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry into the United States — applied to people from Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria and Yemen. As soon as it was signed on Jan. 27, 2017, confusion erupted about who was allowed into the U.S., as did persistent headaches for some travellers from Canada.

The Nexus trusted-traveller cards of about 200 Canadian permanent residents were suddenly cancelled. There were several reports of minorities being turned away at the U.S. border. And a surge of would-be refugees coming north through remote border points continues to this day.

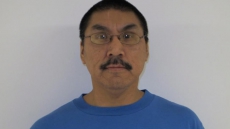

A week after the executive order, Goodale told the House of Commons the Liberal government was trying to ensure Canadian dual-nationals could still use their Nexus cards at the border.

The newly released notes, prepared in February 2017, said card holders "should not be impacted" by the executive order, though Homeland Security was open to hearing about specific examples of people having trouble.

The U.S. records say Canadian officials wanted to know how the order would apply to citizens of a restricted country who were also landed immigrants in Canada.

They appeared to wonder whether a biometric system for keeping track of people entering or leaving the U.S. would apply to Canadian citizens. "How can we work together to discuss alternatives that build on the existing collaboration we have at our shared land border?" Canadian officials asked.

Among the other questions from Ottawa:

— Do measures in the executive order related to U.S. privacy policies affect the "treatment of data" held about Canadians?

— Are there more details about planned standards to prevent "terrorist or criminal infiltration by foreign nationals?"

— What impact, if any, does the order have on the asylum determination system?

Under the Safe Third Country Agreement between Canada and the U.S., an asylum-seeker must claim refugee status in whichever of the two countries they arrive first.

As a result, Canadian officials asked whether a refugee claimant from one of the seven listed countries, turned away by Canada due to the binational agreement, would be permitted to re-enter the U.S.

Goodale spoke by phone with Kelly about the executive order on Jan. 30 and 31, 2017.

Whenever there is a significant policy change affecting cross-border travel, there are questions about the implications for Canadians, said Scott Bardsley, a spokesman for Goodale.

"We are grateful to the United States for their assistance to help us understand the effects of executive orders. Canadians now have a better understanding of these changes."

Beatrice Fenelon, a spokeswoman for Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, said her department was "very satisfied" with the response from Homeland Security.

A revised but largely similar version of the U.S. executive order was introduced about six weeks after the first one ran into judicial roadblocks.

In anticipation of its release, Goodale asked to speak with Kelly on Feb. 27, 2017.

Homeland security notes drafted for Kelly, who has since become Donald Trump's chief of staff, advised that Goodale might "express concerns regarding the increasing numbers of asylum seekers entering Canada between land ports of entry from the United States."

Media reporting linked the northward flow to the initial executive order, sparking calls in Canada to suspend or scrap the Safe Third Country Agreement, the notes mentioned. However, they added that the trend actually predated the order, and a majority of the asylum seekers had a valid visa that would have allowed them to remain in the United States.

The U.S. notes suggested Canada look within its own borders for the cause.

"Recent public statements by senior Canadian officials, and immediate access to Canadian benefits including health care, education, social services, and employment authorization may also be construed as encouraging to potential asylum seekers, as might higher approval rates for asylum seekers generally and specifically from countries of scrutiny such as Somalia, Iraq, Afghanistan, Chad and Eritrea."