TORONTO — Freshly donated blood is not better than older blood when it is transfused into severely ill patients, a new Canadian-led study reports.

The findings should be a relief to Canadian Blood Services and similar agencies, which have faced calls to shorten the length of time blood can be stored before it is transfused.

"When you look at all that evidence, over time it was building pressure on the blood system that fresh was better, that we need to perhaps change policy," said one of the lead authors, Dean Fergusson, a scientist at the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute.

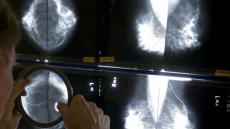

Currently blood can be stored for up to 42 days, though most transfusions involve blood that is about three weeks old. But there has been a growing belief that fresher is better when it comes to transfused blood.

That's because when blood is studied under a microscope, changes are seen as it ages. The assumption has been that those changes would have an impact when older blood is transfused into people. Some animal studies and even observational studies in people have suggested that is likely true.

Observational studies look at things that people do or consume to search for hints about their impacts. In this case, they would have looked at people who got blood transfusions and tried to correlate the age of the blood units with what happened to the recipients.

But observational studies can't prove cause and effect. To determine if something causes something else, scientists use randomized controlled trials. And that is what Fergusson and his colleagues did.

The work involved nearly 2,500 patients in intensive care units in Canada, Britain, France, the Netherlands and Belgium. The study, which was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, was published online Tuesday by the New England Journal of Medicine.

ICU patients who were expected to need transfusions were randomly assigned to get fresh blood — blood that had been stored for less than eight days — or the blood that would normally be sent up from the blood bank. To minimize waste, blood banks will grab the oldest usable blood in the fridge when a transfusion order comes in.

The scientists hypothesized that those who received the fresher blood would do better.

But when they monitored the patients they found no real differences between the two groups. The number of deaths in the two groups were essentially the same. There were no differences between the groups in terms of the length of their hospital stays, the rates of major secondary illnesses they suffered, or other important health measures.

Fergusson had previously conducted a similarly designed trial in premature infants. It too found fresh blood was not better.

"I was amazed then. I thought given all the preliminary evidence and the animal evidence that we would see something.''

He noted that American researchers reported similar findings last year in a study of cardiac surgery patients. But that study, reported at a conference, has not yet been published.