In a first, researchers have shown that a particular kind of artificial light is capable of ensuring that biological rhythms of our body clocks are correctly synchronised despite the absence of sunlight.

The results could help working environments that are dimly to moderately lighted like polar research stations, thermal and nuclear power stations, space missions and offices with no windows.

“An inappropriate exposure to light can throw your entire body clock out of order with consequences for cognitive functions, sleep, alertness, memory, cardiovascular functions, etc.,” cautioned Claude Gronfier from Inserm, a French biomedical and public health research institution.

For nine weeks of the polar winter (no sunlight during the day), the staff of the international polar station Concordia were alternately exposed to a standard white light and a white light enriched with blue wavelengths.

Researchers asked the staff not to change their day-to-day habits, particularly the times they got up and went to bed.

Once a week, samples of saliva were taken in order to measure the rates of melatonin (central hormone) secreted by each of the individuals.

“The results show that an increase in sleep, better reactions and more motivation were observed during the ‘blue’ weeks,” Gronfier noted.

Moreover, while the circadian rhythm tended to shift during the ‘white’ weeks, no disturbance in rhythm was observed during the ‘blue’ weeks.

In addition, the effects did not disappear with the passage of time.

“On a general level, the study shows that an optimised light spectrum enriched with short wavelengths (blue) can enable the circadian system to synchronise correctly and non-visual functions to be activated in extreme situations where sunlight is not available for long stretches of time,” Gronfier explained.

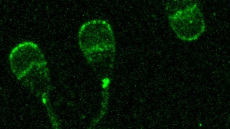

The effectiveness of such lighting is due to the activation of melanopsin-containing ganglion cells discovered in 2002 in the retina.

These photoreceptor cells are basically essential to the transmission of light information to a large number of so-called ‘non-visual’ centres in the brain.

The results were published in the journal Plos One.