Renowned humanitarian, Firdaus Kharas, produces animations that can save lives.

The 2014 Ebola epidemic in West Africa was the largest in history – and it’s far from over. Affecting multiple countries, like Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia, there have been over 20,000 reported cases of the Ebola and around 8,000 deaths in the three countries alone, according to the World Health Organization.

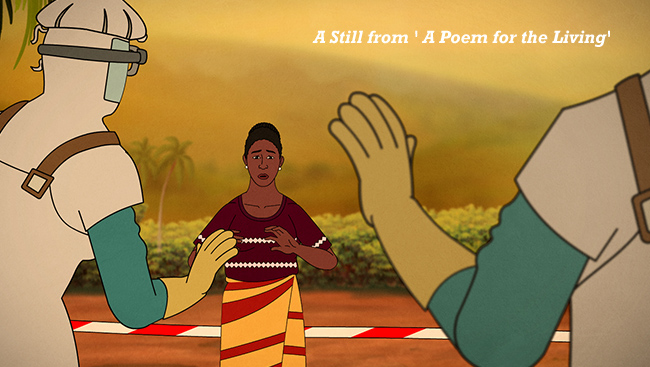

In response to the outbreak of this deadly virus, the humanitarian Firdaus Kharas co-produced an animated video called Ebola: A Poem for the Living. The 4-minute animation is used in West Africa to promote prevention of the disease and has been translated in 15 local dialects. “All of them were voiced in West Africa with children who were 11 to 14 years old. It’s a powerful and emotional piece,” says Kharas, who has made similar educative videos in the past for Malaria and HIV/AIDS. “These diseases are all preventable. Not one person needs to die of [them]. And people die because of lack of information,” he says. A Poem for the Living dispels a lot of the myths and superstitions that exist about Ebola in West Africa, like the one that claims ingesting vinegar prevents the virus.

Ottawa-based Kharas is an old hand at creating non-coercive media for social change. Founder of Chocolate Moose Media, his company produces animations, documentaries and television series that essentially aim to better the human condition by causing behaviour change in individuals and society. Besides the prevention of diseases, Kharas has tackled a multitude of vital issues including gender equality, domestic violence and solar energy in a rather unusual fashion. He addresses them through humour.

“I don’t believe in bashing people over the head and trying to get them to change their opinions,” Kharas says, adding that humour helps him engage the viewer whose behaviour he wants to change. By keeping the animations non-threatening and amusing, he has a greater chance of getting through. He cites his No Excuses campaign as an example, the series of 11 spots on abuse and violence which directly address the abuser. “I’m trying to get them, using humour, to the end of the spot, to the tagline which is the most important part. So you want something that amuses you, and you want something that you will remember.”

Incorporating humour in his work is a constant challenge for Kharas, given the nature of the issues he addresses. A bigger challenge, however, is ensuring that the humour is universal. With his work translated in over 100 languages, and seen by over a billion people, Kharas’s animations need to allow for cross-cultural communication. “I have a list of over 50 barriers that I have to work through in creating each and every spot,” he says. Barriers like language, ethnicity, religion, economic and political status and levels of education may be what distinguish people, but they are also what separate them. “The advantage of animation is that it gets over many of these barriers,” Kharas says. “You know what you are seeing is not real, so you are more accepting of the messages.”

Kharas’s acclaimed series The Three Amigos, which won 30 international awards including a prestigious Peabody Award, is the perfect example of this. Designed to stop the spread of HIV/AIDS, the 20 spots feature three animated talking condoms and these comedic spots have been broadcast world-wide – including in some of the more conservative Muslim countries. “People say to me, how do you get condoms on the Iranian National Television,” says Kharas. “Well, you get them because they are animated.”

So what led Kharas to pursue this kind of animated activism? Even well before his career of media production, he had dedicated his life to improving the human condition. His graduate thesis examined the convention against torture; he served as the executive director of the United Nations Association in Canada, and as the Assistant Deputy Chairman of the Immigration and Refugee Board, he helped clear the backlog of more than 100,000 refugee claims. However, his desire to make a difference can be traced further back to his childhood. Born in Calcutta into an upper-middle class family, with a mother who headed a national NGO, Kharas was aware of his privileged position from a very young age. When he was fifteen, he and a friend set up a school in a slum in Mumbai, and taught everything they had learnt at school during the week. “Sometimes we had like 200 kids come just to a single class.”

Kharas’s efforts to better the world have not gone unnoticed; he has been recognised with over 70 awards for his humanitarian work and he continues to do more. He is currently working on creating an animated short series in Arabic on the rights of children with diabetes. The Middle East has the highest rates of diabetes in the world, he explains, and no one has addressed the rights these children have. “The right to test themselves, to go to the bathroom whenever they want, the right to play sports and not be excluded, I’m making 15 animated shorts on that,” he says.

A champion of human rights, Kharas addresses the issues that get overlooked, sidelined or silenced. “People ask me what is the bottom line of what you do, and I say, I create media to better the human condition.”